- Home

- Blake Mycoskie

Start Something That Matters

Start Something That Matters Read online

As of press time, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Random House, Inc., is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Random House.

Copyright © 2011 by Blake Mycoskie

Reading group guide copyright © 2012 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

SPIEGEL & GRAU and Design is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

The photo on this page is courtesy of Lauren Garceau.

The photo on this page is courtesy of Chelsea Diane Photography.

All other photos are courtesy of the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mycoskie, Blake.

Start something that matters / Blake Mycoskie.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60352-8

1. Marketing—Social aspects. 2. Social entrepreneurship. I. Title.

HF5414.M93 2011

658.4′08—dc22 2011009768

www.spiegelandgrau.com

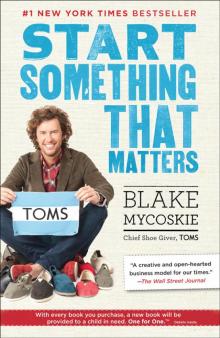

Jacket design: Greg Mollica

Jacket photographs: Kwaku Alston

v3.1

SUCCESS

To laugh often and love much

To win the respect of intelligent people

and the affection of children

To earn the appreciation of honest critics

endure the betrayal of false friends

To appreciate beauty

To find the best in others

To leave the world a bit better

whether by a healthy child,

a garden patch, or a redeemed social condition

To know even one life has breathed easier

because you have lived.

This is to have succeeded.

[Often attributed to Elisabeth-Anne Anderson Stanley]

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

author’s note

one the TOMS story

two find your story

three face your fears

four be resourceful without resources

five keep it simple

six build trust

seven giving is good business

eight the final step

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Reader’s Guide

author’s note

Friend,

The reason for this book is simple. I want to share the knowledge we have gained since starting TOMS, and from the amazing group of entrepreneurs and activists I have met along the way whom I have learned so much from. Their stories, as well as mine, are told in this book with the aim of inspiring, entertaining, and challenging you to start something that matters.

In addition to sharing the lessons learned, 50 percent of my proceeds from this book will be used to support others through the Start Something That Matters Fund. It is my dream that this commitment and this book will be a catalyst for others as they try and make a positive impact on the world.

Thank you for joining us in this great adventure.

Carpe diem,

Blake

July 7, 2011

Colorado Mountains

Be the change you want to see in the world.

—MAHATMA GANDHI

In 2006 I took some time off from work to travel to Argentina. I was twenty-nine years old and involved in my fourth entrepreneurial start-up: an online driver-education program for teens that used only hybrid vehicles and wove environmental education into our curriculum—earth-friendly innovations that set us apart from the competition.

We were at a crucial moment in the business’s development—revenue was growing, and so were the demands on our small staff—but I had promised myself a vacation and wasn’t going to back out. For years I’ve believed that it’s critical for my soul to take a vacation, no matter how busy I am. Argentina was one of the countries my sister, Paige, and I had sprinted through in 2002 while we were competing on the CBS reality program The Amazing Race. (As fate would have it, after thirty-one days of racing around the world, we lost the million-dollar prize by just four minutes; it’s still one of the greatest disappointments of my life.)

When I returned to Argentina, my main mission was to lose myself in its culture. I spent my days learning the national dance (the tango), playing the national sport (polo), and, of course, drinking the national wine (Malbec).

I also got used to wearing the national shoe: the alpargata, a soft, casual canvas shoe worn by almost everyone in the country, from polo players to farmers to students. I saw this incredibly versatile shoe everywhere: in the cities, on the farms, in the nightclubs. An idea began to form in the back of my mind: Maybe the alpargata would have some market appeal in the United States. But as with many half-formed ideas that came to me, I tabled it for the moment. My time in Argentina was supposed to be about fun, not work.

Toward the end of my trip, I met an American woman in a café who was volunteering with a small group of people on a shoe drive—a new concept to me. She explained that many kids lacked shoes, even in relatively well-developed countries like Argentina, an absence that didn’t just complicate every aspect of their lives but also exposed them to a wide range of diseases. Her organization collected shoes from donors and gave them to kids in need—but ironically the donations that supplied the organization were also its Achilles’ heel. Their complete dependence on donations meant that they had little control over their supply of shoes. And even when donations did come in sufficient quantities, they were often not in the correct sizes, which meant that many of the children were still left barefoot after the shoe drop-offs. It was heartbreaking.

I spent a few days traveling from village to village, and a few more traveling on my own, witnessing the intense pockets of poverty just outside the bustling capital. It dramatically heightened my awareness. Yes, I knew somewhere in the back of my mind that poor children around the world often went barefoot, but now, for the first time, I saw the real effects of being shoeless: the blisters, the sores, the infections—all the result of the children not being able to protect their young feet from the ground.

I wanted to do something about it. But what?

My first thought was to start my own shoe-based charity, but instead of soliciting shoe donations, I would ask friends and family to donate money to buy the right type of shoes for these children on a regular basis. But, of course, this arrangement would last only as long as I could find donors; I have a large family and lots of friends, but it wasn’t hard to see that my personal contacts would dry up sooner or later. And then what? What would happen to the communities that had begun to rely on me for their new shoes? These kids needed more than occasional shoe donations from strangers—they needed a constant, reliable flow.

Then I began to look for solutions in the world I already knew: business and entrepreneurship. I had spent the previous ten years launching businesses that solved problems creatively, from delivering laundry to college students to starting an all-reality cable-TV channel to teaching teenagers driver education online. An idea hit me: Why not create a for-profit business to help provide shoes for these children? Why not come up with a solution that guaranteed a constant flow of shoes, rather than being dependent on kind people making donations? In other words, maybe the solution was in entrepreneurship, not

charity.

I felt excited and energized and shared those feelings with Alejo, my Argentinian polo teacher and new friend: “I’m going to start a shoe company that makes a new kind of alpargata. And for every pair I sell, I’m going to give a pair of new shoes to a child in need. There will be no percentages and no formulas.”

It was a simple concept: Sell a pair of shoes today, give a pair of shoes tomorrow. Something about the idea felt so right, even though I had no experience, or even connections, in the shoe business. I did have one thing that came to me almost immediately: a name for my new company. I called it TOMS. I’d been playing around with the phrase “Shoes for a Better Tomorrow,” which eventually became “Tomorrow’s Shoes,” then TOMS. (Now you know why my name is Blake but my shoes are TOMS. It’s not about a person. It’s about a promise—a better tomorrow.)

I asked Alejo if he would join the mission, because I trusted him implicitly and, of course, I would need a translator. Alejo jumped at the opportunity to help his people, and suddenly we were a team: Alejo, the polo teacher, and me, the shoe entrepreneur who didn’t know shoes and didn’t speak Spanish.

I’ve been keeping a journal since I was a teenager. Here’s a sketch that I drew in the earliest days of TOMS.

We began working out of Alejo’s family barn, when we weren’t off meeting local shoemakers in hopes of finding someone who would work with us. We described to them precisely what we wanted: a shoe like the alpargata, made for the American market. It would be more comfortable and durable than the Argentine version, but also more fun and stylish, for the fashion-conscious American consumer. I was convinced that a shoe that had been so successful in Argentina for more than a century would be welcomed in the United States and was surprised that no one had thought of bringing this shoe overseas before.

Most of the shoemakers called us loco and refused to work with us, for the hard-to-argue-with reason that we had very little idea of what we were talking about. But finally we found someone crazy enough to believe: a local shoemaker. For the next few weeks, Alejo and I traveled hours over unpaved and pothole-riddled roads to get to his “factory”—a room no bigger than the average American garage, with a few old machines and limited materials.

Each day ended with a long discussion about the right way to create our alpargata. For instance, I was afraid it wouldn’t sell in the traditional alpargata colors of navy, black, red, and tan, so I insisted we create prints for the shoes, including stripes, plaids, and a camouflage pattern. (Our bestselling colors today? Navy, black, red, and tan. Live and learn.) The shoemaker couldn’t understand this—nor could he figure out why we wanted to add a leather insole and an improved rubber sole to the traditional Argentine design.

I simply asked him to trust me. Soon we started collaborating with some other artisans, all working out of dusty rooms outfitted with one or two old machines for stitching the fabric, and surrounded by roosters, burros, and iguanas. These people had been making the same shoes the same way for generations, so they looked at my designs—and me—with understandable suspicion.

We then decided to test the durability of the outsole material we were using. I would put on our prototypes and drag my feet along the concrete streets of Buenos Aires with Alejo walking beside me. People would stop and stare; I looked like a crazy person. One night I was even stopped by a policeman who thought I was drunk, but Alejo explained that I was just a “little weird,” and the officer let me be. Through this unorthodox process, we were able to discover which materials lasted longest.

Alejo and I worked with those artisans to get 250 samples made, and these I stuffed into three duffel bags to bring back to America. I said good-bye to Alejo, who by now had become a close friend: No matter how furiously we argued, and we did argue, each evening would end with an agreement to disagree, and each morning we’d resume our work. In fact, his entire family had stood by me, even though none of us had any idea what would happen next.

Soon I was back in Los Angeles with my duffel bags of modified alpargatas. Now I had to figure out what to do with them. I still didn’t know anything about fashion, or retail, or shoes, or anything relating to the footwear business. I had what I thought was a great product, but how could I get people to actually pay money for it? So I asked some of my best female friends to dinner and told them the story: my trip to Argentina, the shoe drive, and, finally, my idea for TOMS. Then I showed them the goods and grilled them: Who do you think the market is for the shoes? Where should I sell them? How much should we charge? Do you like them?

Luckily, my friends loved the story, loved the concept of TOMS, and loved the shoes. They also gave me a list of stores they thought might be interested in selling my product. Best, they all left my apartment that night wearing pairs they’d insisted on buying from me. A good sign—and a good lesson: You don’t always need to talk with experts; sometimes the consumer, who just might be a friend or acquaintance, is your best consultant.

By then I had gone back to working at my current company, the driver-education business, so I didn’t have a great deal of time to devote to hawking shoes. At first I thought it wouldn’t matter and that I could get everything done via email and phone calls in my spare time.

That idea got me nowhere. One of the first of many important lessons I learned along the way: No matter how convenient it is for us to reach out to people remotely, sometimes the most important task is to show up in person.

So one day I packed up some shoes in my duffel bag and went to American Rag, one of the top stores on the list my friends had compiled, and asked for the shoe buyer. The woman behind the counter told me that I was in luck, because on this particular day the buyer happened to be at the store. And it turned out that she had time to see me. I went in and told her the TOMS story.

Every month this woman saw, and judged, more shoes than you can imagine—certainly more shoes than American Rag could ever possibly stock. But from the beginning, she realized that TOMS was more than just a shoe. It was a story. And the buyer loved the story as much as the shoe—and knew she could sell both of them.

TOMS now had a retail customer.

Another big break followed soon afterward. Booth Moore, the fashion writer for the Los Angeles Times, heard about our story, loved it—and the shoes—and interviewed me and wrote an article.

One Saturday morning not long after, I woke up to see my BlackBerry spinning around on a table like it was possessed by demons. I had set the TOMS website to email me every time we received an order, which at the time had been about once or twice a day. Now my phone was vibrating uncontrollably, so much so that, just as suddenly, the battery died. I had no idea what was wrong, so I left it on the table and went out to meet some friends for brunch.

Once I arrived at the restaurant, I saw the front page of the Los Angeles Times’s calendar section: It was Booth Moore’s story. TOMS was headlines! And that’s why my BlackBerry had been spinning so crazily: It turned out we already had 900 orders on the website. By the end of the day, we’d received 2,200.

That was the good news. The bad news was that we had only about 160 pairs of shoes left sitting in my apartment. On the website we had promised everyone four-day delivery. What could we do?

Craigslist to the rescue. I quickly wrote up and posted an ad for interns and by the next morning had received a slew of responses, out of which I selected three excellent candidates, who began working with me immediately. One of them, Jonathan, a young man with a Mohawk haircut, spent his time calling or emailing the people who had ordered shoes to let them know their orders weren’t coming anytime soon, because we didn’t have any inventory—in fact, they might have to wait as long as eight weeks before we had more. And yet only one person out of those 2,200 initial orders canceled, and that was because she was leaving for a semester abroad. (Jonathan, by the way, is still with TOMS, working on our global logistics—and he still has the Mohawk.)

Now I had to return to Argentina to make more shoes. I met with Alejo and the lo

cal shoemaker, and we immediately set out to manufacture 4,000 new pairs. We still had to convince the shoemakers to construct our design; we had to find suppliers willing to sell us the relatively small amounts of fabric needed to fulfill the orders; and, because no one person or outfit could construct the entire shoe from start to finish, we had to drive all over the greater Buenos Aires area ferrying fabrics to stitchers, unfinished shoes to shoemakers, and so on. That meant spending half the day on the very busy streets of the city in our car, driving like madmen. Alejo, who was used to it, was talking on two cellphones at once while weaving in and out of traffic as I gripped the seat, white-knuckled. I was scared out of my mind. Not even running a driver-ed course in America could prepare me for this.

The one and only Alejo Nitti. Perhaps the only polo player turned accountant turned shoemaker that you’ll ever meet.

In the meantime, back home, publicity kept growing as the Los Angeles Times article sparked more coverage. The next big hit came when Vogue magazine decided to do a spread on TOMS, although I doubt they knew our company consisted of three interns and me working out of my apartment. In the magazine, our forty-dollar canvas flats were being featured next to Manolo Blahnik stilettos that sold for ten times as much. After Vogue, other magazines, such as Time, People, O, Elle, and even Teen Vogue, wrote us up.

Meanwhile, our retail customer base was expanding beyond the trendy Los Angeles stores to include national powerhouses such as Nordstrom, Whole Foods, and Urban Outfitters. Soon, celebrities like Keira Knightley, Scarlett Johansson, and Tobey Maguire were spotted around town wearing TOMS. Step by step, our product was making its way across the country, and our story began to spread.

We ended up selling 10,000 pairs of shoes that first summer—all out of my Venice apartment, a fact we had to hide from my landlady because I wasn’t at all certain that my lease allowed for running a shoe company out of my living room. She was something of an oddball and would occasionally walk into the apartment unannounced. Luckily, her car had a terrible muffler that announced her presence from a block away. Whenever anyone heard that racket, we’d perform an extreme cleanup and all the interns would hide in my bedroom; when she showed up, there was no sign that a full-fledged business was being run out of a residential apartment. Sometimes we’d even hold drills just to make sure we could clean everything up within a few minutes.

Start Something That Matters

Start Something That Matters